Fan-out Sidekiq Jobs to Manage Large Workloads

November 09, 2023 📬 Get My Weekly Newsletter ☞

Performing a resilient operation on bulk data can be challenging, especially if the operation relies on a third party. You can safely do this by fanning out the work to idempotent background jobs that operate on only one piece of data at a time. Those jobs can retry independently as needed, making the entire operation more easy to manage. This post will show an example of how that works and why you might want to use this pattern.

Fanning out is a way to perform work in parallel batches instead of inside a loop. Executing an operation this way provides more control and more resilience. Doing this well requires a combination of both job and database design.

Simple Domain of Charging Subscriptions

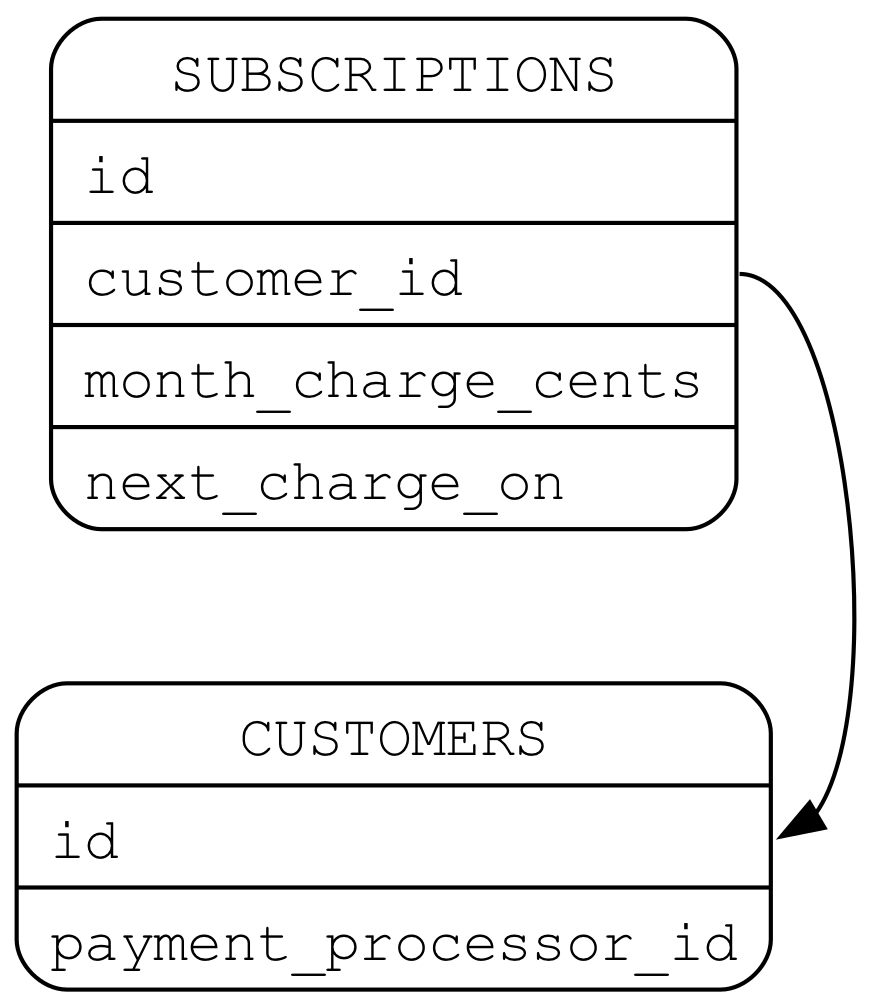

Let’s take simplified domain of charging customers a subscription each month. Let’s say we have a subscriptions table that has

a customer ID, an amount to charge each month, and the date on which to charge them. Each month when we charge them, we’ll

update that date to be the next month. Let’s assume there is a customers table that has some sort of identifier to a third

party payment processor as well.

A simple way of doing this is to loop over each subscription, check if next_charge_on is today and, if so, charge the

customer. Assume there is a ThirdPartyPaymentProcessor class that handles talking to our credit card payment service.

We’ll put this into a Sidekiq job and arrange for it to run every day.

class ChargeSubscriptionsJob

include Sidekiq::Job

def perform

payment_processor = ThirdPartyPaymentProcessor.new

Subscription.where(next_charge_on: Date.today).find_each do |subscription|

payment_processor.charge!(

subscription.customer.payment_processor_id,

subscription.monthly_charge_cents

)

subscription.update!(next_charge_on: Date.today + 1.month)

end

end

end

Even at a moderate scale, this can become difficult to manage.

Difficulties with Long-Running Batch Jobs

Suppose our payment processor experiences an outage partway through processing. The job will fail and be retried. The subscription being charged during the failure may or may not have been charged. If it was, retrying this job will charge it again.

What if we have so many subscriptions that we can’t charge them all in one job? Most payment processors take a few seconds to complete a charge. If we had 1,000 customers to charge on any given day, that means this job would take about an hour to complete.

If you were to deploy, or cycle infrastructure (as is common with cloud-hosted services) it could fail partway through. What if there is some bug or problem with the data such that a particular subscription always causes a failure? If the job processes subscriptions in the same order, it would always fail at the errant subscription, preventing the entire batch from ever completing (a so-called “poison pill”).

Large jobs that operate on a lot of data and run for a long time are magnets for failures. It can be often difficult to unwind what went wrong and correct it. If we could break up the logic into manageable chunks, that might make it easier.

Breaking up Batch Operations to Small Chunks

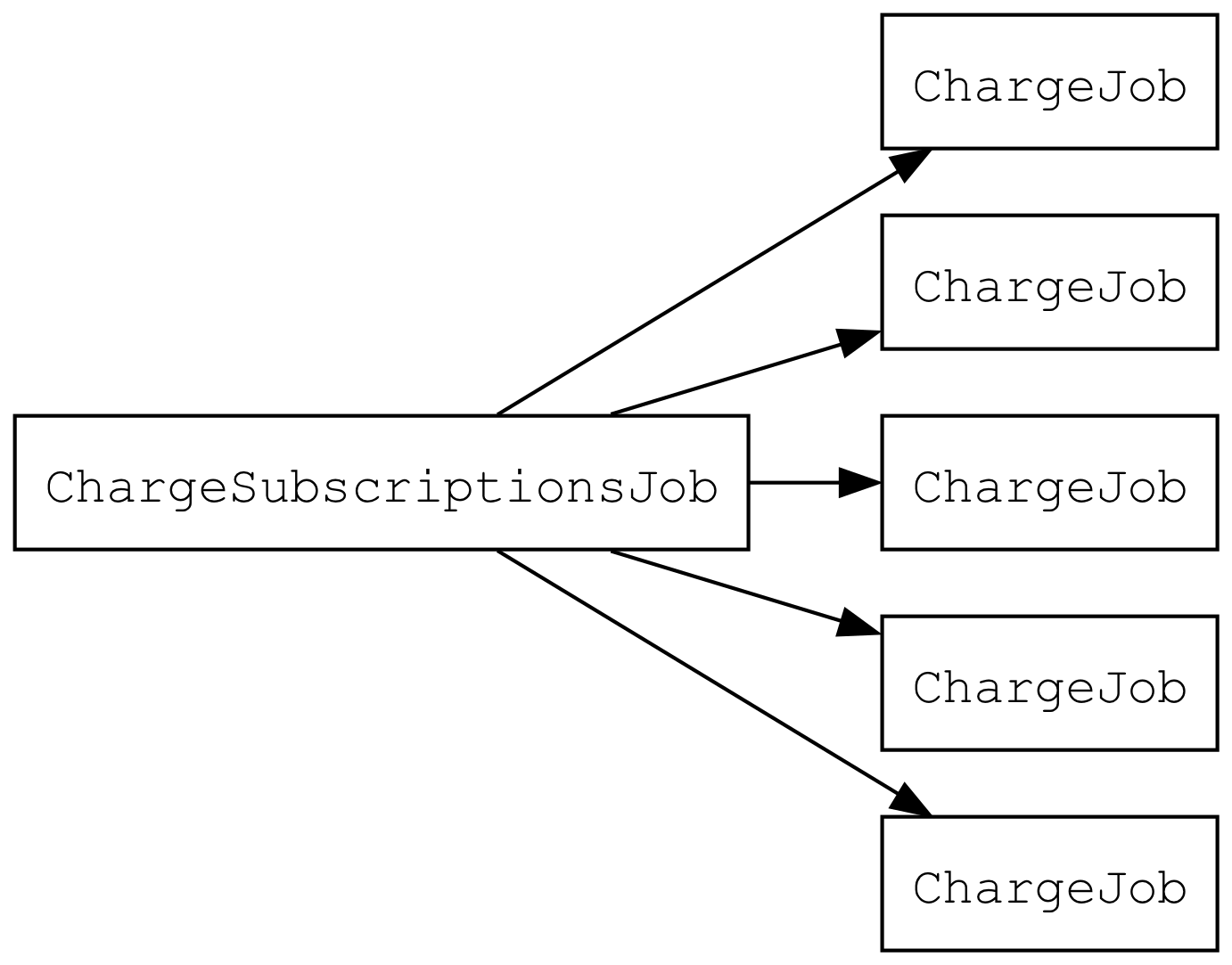

Let’s keep ChargeSubscriptionsJob selecting subscriptions to charge but, instead of charging them, it queues a job for each subscription to charge. This is called “fanning out” because it’s usually diagrammed like so, which looks like fanning out playing cards:

Let’s try it. ChargeSubscriptionsJob will queue ChargeJob like so:

class ChargeSubscriptionsJob

include Sidekiq::Job

def perform

Subscription.where(next_charge_on: Date.today).find_each do |subscription|

ChargeJob.perform_later(subscription_id) # <---

subscription.update!(next_charge_on: Date.today + 1.month)

end

end

end

The ChargeJob contains all the code we just removed:

class ChargeJob

include Sidekiq::Job

def perform(subscription_id)

payment_processor = ThirdPartyPaymentProcessor.new

subscription = Subscription.find(subscription_id)

payment_processor.charge!(

subscription.customer.payment_processor_id,

subscription.monthly_charge_cents

)

end

end

Now, ChargeSubscriptionsJob doesn’t depend on the payment processor. It just depends on the database and the Redis being used

for Sidekiq. These are under our control and less likely to fail. And, since we only update next_charge_on after we

successfully queue ChargeJob, if ChargeSubscriptionsJob gets retried, it won’t queue the same subscription twice.

This also means that any problematic subscription won’t spoil the entire batch. The so-called poison pill subscription would continue to fail, but each time it got retried, other subscriptions would get processed first. This failed job no longer prevents the entire batch from failing, turning it into just another failed job and not a traditional poison pill.

Of course, changing our design to fan out jobs introduce other failure modes we need to address.

Failures When Fanning Out

If you think about our updated design, the ChargeJob instances queued to Sidekiq are the only place we have a record of what

subscriptions to charge and how much to charge them. Sidekiq is a great job processor, but it’s not a database.

What this means is that if monthly_charge_cents changed after it queued a ChargeJob, but before it was processed, we’d charge

the wrong amount. Worse, if we lost Redis, we could lose some ChargeJobs and have no idea what subscriptions needed to get

charged. Sidekiq does its best to avoid this situation, but Redis is not a resilient database like Postgres.

What we should do is use our database to store information that weit need to persist, have our Sidekiq jobs fetch the data they

need from there. The ChargeJob is really an intention to charge money that, when processed, becomes realized. We should

store that intention in our database.

Using the Database To Store Operational Data

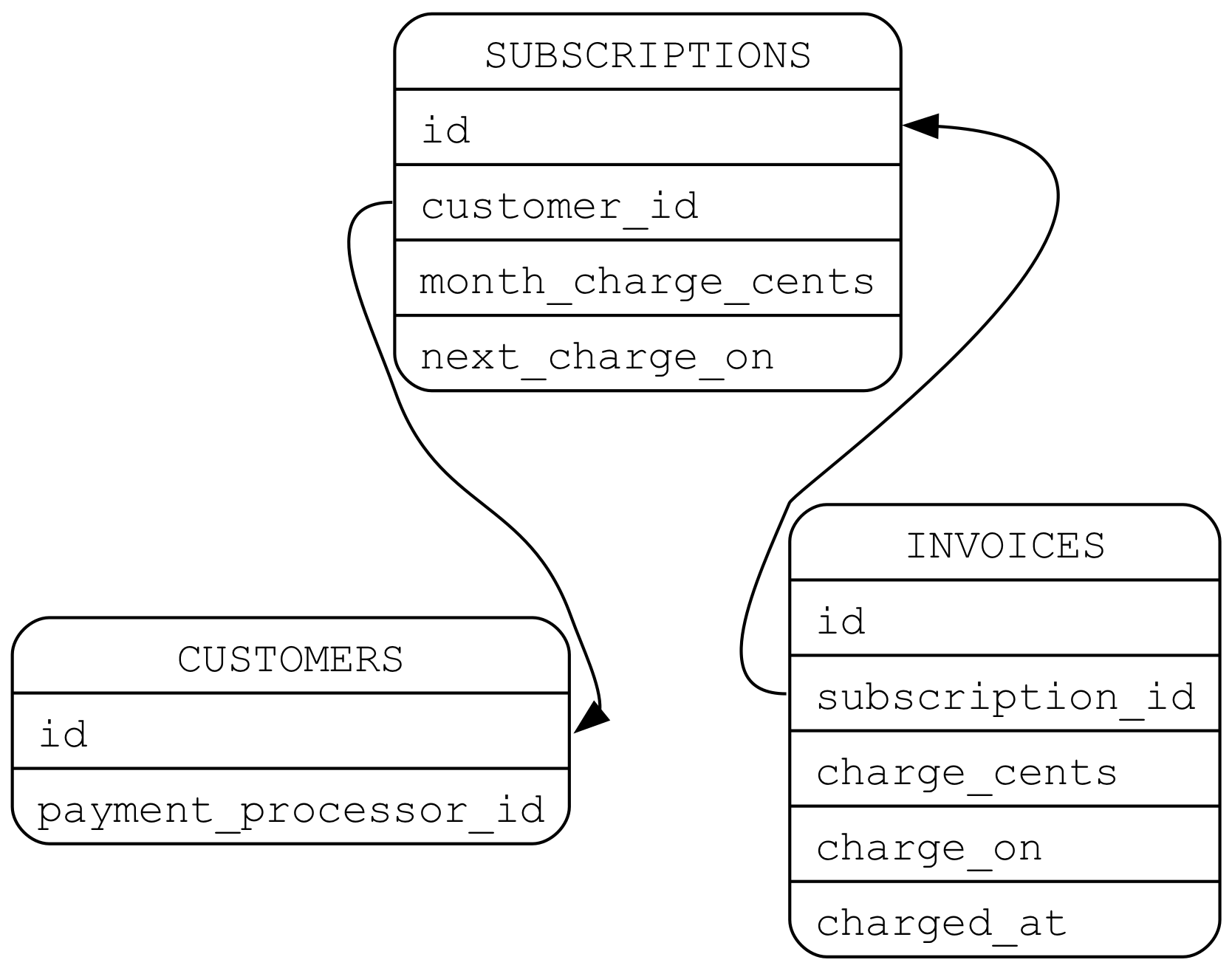

Let’s call this an invoice. It’ll reference a subscription, hold the amount to charge, the original charge_on date, and a

nullable value for when the charge was completed:

Now, ChargeSubscriptionsJob will create an invoice and ChargeJob will accept an invoice id to charge. Because

ChargeSubscriptionsJob now has to both create the invoice and update the Subscription, we want to perform both of those

inside a database transaction. That way, either both changes are made or neither are, and we don’t end up in a half-updated

state.

class ChargeSubscriptionsJob

include Sidekiq::Job

def perform

Subscription.where(next_charge_on: Date.today).find_each do |subscription|

ActiveRecord::Base.transaction do

invoice = subscription.invoices.create!(

charge_on: subscription.charge_on,

charge_cents: subscription.monthly_charge_cents,

charged_at: nil

)

subscription.update!(

next_charge_on: Date.today + 1.month

)

end

ChargeJob.perform_later(invoice_id)

end

end

end

Note that ChargeJob is now queued after all the database updates. While, in theory, we could queue it right after creating

the invoice, that would require doing so inside an open database transaction. This is bad. At even moderate scale, this can

cause the locks required to keep the transaction open to be open for too long and have a cascading effect on the system. This

effect can be extremely hard to diagnose back to the open transaction.

This has implications we’ll get to in a minute, but let’s see the updated ChargeJob:

class ChargeJob

include Sidekiq::Job

def perform(invoice_id)

payment_processor = ThirdPartyPaymentProcessor.new

invoice = Invoice.find(invoice_id)

if invoice.charged_at.present?

Rails.logger.info "Invoice #{invoice.id} already charged"

return

end

customer = invoice.subscription.customer

payment_processor.charge!(

customer.payment_processor_id,

invoice.charge_cents

)

invoice.update!(charged_at: Time.zone.now)

end

end

ChargeJob is mostly the same, except it now updated the invoice to indicate it was charged. It also checks to make sure the

invoice wasn’t already charged.

This now includes everything needed to manage these jobs inside the database. If we lost Redis entirely, we can look at any

invoice where charged_at was null and know that it hadn’t been charged. In fact, we could eliminate the need for

ChargeSubscriptionsJob to queue ChargeJobs entirely by creating a new job called ChargeOutstandingInvoicesJob.

Using the Database to Drive Job Queueing

First, we remove the call to ChargeJob.perform_later:

class ChargeSubscriptionsJob

include Sidekiq::Job

def perform

Subscription.where(next_charge_on: Date.today).find_each do |subscription|

ActiveRecord::Base.transaction do

invoice = subscription.invoices.create!(

charge_on: subscription.charge_on,

charge_cents: subscription.monthly_charge_cents,

charged_at: nil

)

subscription.update!(

next_charge_on: Date.today + 1.month

)

end

# XXX ChargeJob.perform_later(invoice_id)

end

end

end

This means that ChargeSubscriptionsJob is always safe to retry under any circumstance, since it will always pick up where it

left off—as long as it completes all subscriptions before the end of the day.

To get the invoices charged, ChargeOutstandingInvoicesJob will look like so:

class ChargeOutstandingInvoicesJob

include Sidekiq::Job

def perform_at

Invoice.where(charged_at: nil).find_each do |invoice|

ChargeJob.perform_later(invoice.id)

end

end

end

Is ChargeOutstandingInvoicesJob safe to retry? Yes, with a qualification. Since ChargeJob checks that charged_at is null, this avoids a race condition where a retry of ChargeOutstandingInvoicesJob could queue two ChargeJobs for the same invoice.

What is a problem with ChargeJob regardless of how ChargeOutstandingInvoicesJob (or ChargeSubscriptionsJob) is implemented

is that the third party payment processor call needs to be idempotent. We need to make sure that happens exactly once.

This is covered in detail in the book. There is a sample app that demonstrates this exact problem, and a detailed discussion of how to manage it. The book shows you some code to address it, and you can see it working with the example app.

Addendum - Bulk Queueing API

If you aren’t familiar with Sidekiq’s Bulk Queueing API, a better way to

implement ChargeOutstandingInvoicesJob would be to bulk queue the ids in batches of 1000, like so:

class ChargeOutstandingInvoicesJob

include Sidekiq::Job

def perform_at

array_of_job_args = Invoice.

where(charged_at: nil). # Get all not charged

pluck(:id). # Get only their ids

zip # turn each element into

# a single-element array

# batch size is 1000 by default

ChargeJob.perform_bulk(array_of_job_args)

end

end

This is a more efficient—and thus less error prone—way to queue a bunch of jobs based on the results of a database query.

array_of_job_args is an array where each element represents an invoice, and those elements are themselves arrays

that contain a single argument: the invoice’s id.