Wrap Third Party APIs in Service Wrappers to Simplify Your Code

October 31, 2022 📬 Get My Weekly Newsletter ☞

The app I work on has a lot of API integrations. These API calls are often tied into various business processes. By wrapping an adapter around each API, presenting only the features of that API my app needs, I can more easily manage and test my app. It also provides clear documentation about how my app uses each API. I’ve heard this called a service wrapper and it’s incredibly useful.

Third Party Integrations Make Everything Complicated

Integrating with a third party API carries a host of problems, but most of the boil down to:

- Any codepath that uses the API can be hard to test since you have to mock HTTP calls or the client library, both of which are often complex.

- The API has many more features than you need, often implemented in a way that makes your use-case overcomplicated. We’ve all built massive hashes that contain only a few bits of relevant data in them, just to satisfy a highly-generalized API call.

Stripe’s Payment Intents API is a great example. It’s highly flexible, handling many use-cases. But, if all you need to do is charge a card on file, you end up with a somewhat complicated call no matter what.

The service wrapper I’ll demonstrate below will wrap Stripe in a simplified—but still Stripe-like—API that only does what we need. The resulting class creates a boundary that is easier to mock for upstream tests and easier to test and manage for assuring a good integration.

Let’s see the problem directly and derive the service wrapper.

A Naive Integration with Everything Inline

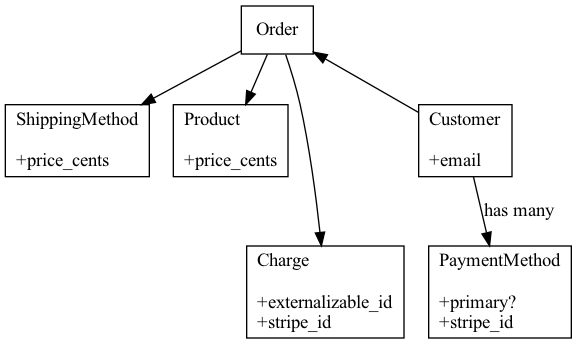

Suppose our company, Example Co, sells products to customers. We have a routine that is triggered when an order ships. That routine will charge the customer the price of the order plus shipping, as well as performing some basic bookkeeping. The domain is outlined in this figure:

The code will accept an order, which is related to a customer, a product, and a

shipping_method. The customer also has several payment_method objects representing cards

they have added previously. One is marked primary, and that’s what we want to use here.

We’ll create a charge that represents our charge with Stripe, and that will relate to the order, plus record Stripe’s ID. A charge also has an externalizable_id which uniquely identifies the charge in our system so we can share it with Stripe (but not expose our database keys).

Here’s the method with all the code in it in one big blob. This method looks like what you might produce during TDD before you’ve done any refactoring:

def on_order_shipped(order)

customer = order.customer

payment_method = customer.payment_methods.primary

product = order.product

shipping_cost = order.shipping_method.price_cents

total_price = product.price_cents + shipping_cost

charge = Charge.create!(

order: order,

amount_cents: total_price

)

stripe_args = {

currency: "usd",

confirm: true,

off_session: true,

amount: total_price,

description: "Purchase of #{product.name}"

receipt_email: customer.email,

payment_method: payment_method.id,

metadata: {

example_co_id: charge.externalizable_id,

}

}

payment_intent = Stripe::PaymentIntent.create(args)

if payment_intent.charges.count != 1

# Imagine a more sophisticated error handling

# strategy here...

raise "Expected exactly one charge"

end

stripe_charge = payment_intent.charges.first

charge.update!(stripe_id: stripe_charge.id)

end

This method is a bit long, and the simplest thing we can do to clean it up is to extract the Stripe stuff into a private method, like so:

def on_order_shipped(order)

customer = order.customer

payment_method = customer.payment_methods.primary

product = order.product

shipping_cost = order.shipping_method.price_cents

total_price = product.price_cents + shipping_cost

charge = Charge.create!(

order: order,

amount_cents: total_price

)

stripe_charge = charge_stripe(customer, # <---

payment_method, # <---

total_price, # <---

product, # <---

charge) # <---

charge.update!(stripe_id: stripe_charge.id)

end

private

def charge_stripe(customer,

payment_method,

total_price,

product,

charge)

stripe_args = {

currency: "usd",

confirm: true,

off_session: true,

amount: total_price,

description: "Purchase of #{product.name}"

receipt_email: customer.email,

payment_method: payment_method.id,

metadata: {

example_co_id: charge.externalizable_id,

}

}

payment_intent = Stripe::PaymentIntent.create(args)

if payment_intent.charges.count != 1

raise "Expected exactly one charge"

end

payment_intent.charges.first

end

Although this cleans up the code for on_order_shipped, it’s still problematic to test. We have

to test that we are using the right card, calculating the proper price, and calling Stripe in just the right way (as well as handling errors from Stripe).

To mock our call to Stripe requires assembling a large hash and creating a mock object for Stripe to return that wraps its charge id. Or, we have to set up an HTTP-mocking system like VCR, which is unpleasant and flaky. None of this has to do with the core logic of the routine, which is calculate the price.

The problem is that the seam created by our private method isn’t right.

A Boundary At the Wrong Place Makes Things Worse

Our private method may seem like it could be the public method of a new class. We can then mock that class to test our method and not worry about Stripe’s API. Since this will wrap our integration with Stripe (a web service), let’s call this class a service wrapper. Here’s what that looks like:

class Stripe::ServiceWrapper

def charge(customer,

payment_method,

total_price,

product,

charge)

# all the code from before

end

end

This is an improvement, but it uncovers a third behavior of the original method, which is to

map our domain to Stripe’s. That mapping is now inside Stripe::ServiceWrapper, and it’s

tightly coupled to the use-case of charging for a shipped order.

This creates an immediate problem in that we need to create several Active Records just to test this method, but it’s also not a very useful method for charging credit cards for other reasons than the shipment of an order.

We’ve created the wrong boundary. We need a boundary between our domain and Stripe’s. Let’s try to create that.

Service Wrappers Should be in the Domain of the Service, not Your App

Let’s change the service wrapper so that it does not map our domain to Stripe’s and instead acts like a simplified API from Stripe itself. We don’t need the full power of the payment intents API, we only need to charge an amount to a card and send a receipt email.

Meaning, we want a method that accepts:

- A Stripe payment method ID

- An amount to charge

- An email where a receipt will be sent

- A description to go in that email

- Some sort of ID from our system to go into the metadata

Our routine uses the payment intents API, and in addition to creating a payment intent, it also “confirms” it, which is Stripe’s way of saying it will actually charge the card.

Here it is written in the domain of Stripe:

class Stripe::ServiceWrapper

def create_and_confirm_payment_intent(

payment_method_id:,

receipt_email:,

description:,

amount_cents:,

example_co_id:)

args = {

currency: "usd",

confirm: true,

off_session: true,

amount: amount_cents,

description: description,

receipt_email: receipt_email,

payment_method: payment_method_id,

metadata: {

example_co_id: example_co_id,

}

}

payment_intent = Stripe::PaymentIntent.create(args)

if payment_intent.charges.count != 1

# Imagine a more sophisticated error handling

# strategy here...

raise "Expected exactly one charge"

end

charge = payment_intent.charges.first

charge.id

end

end

Now, Stripe::ServiceWrapper has nothing to do with our domain. It’s just a much simpler method

to charge a card in Stripe. The argument names use Stripe’s domain, save for example_co_id. This is preferable to a metadata hash because this value will show up in Stripe’s web UI and it’s part of the Stripe API we are creating. It’s specific to us on purpose.

on_order_shipped will now call create_and_confirm_payment_intent, but the job of mapping our domain to Stripe’s will revert back to on_order_shipped:

def on_order_shipped(order)

customer = order.customer

payment_method = customer.payment_methods.primary

product = order.product

shipping_cost = order.shipping_method.price_cents

total_price = product.price_cents + shipping_cost

charge = Charge.create!(

order: order,

amount_cents: total_price

)

service_wrapper = Stripe::ServiceWrapper.new

stripe_id = service_wrapper.create_and_confirm_payment_intent(

payment_method_id: payment_method.id,

receipt_email: customer.email,

description: description,

amount_cents: total_price,

example_co_id: charge.externalizable_id)

charge.update!(stripe_id: stripe_id)

end

Note that our invocation now provides a clear mapping of our domain to Stripe’s, in the context

of the operation being performed inside on_order_shipped. The service wrapper doesn’t need access to our domain objects, nor we to theirs. This is a good boundary between the two systems.

I’ve repeated this pattern of extraction over and over again that I now start any code requiring an API integration with a service wrapper just like the one we created.

Four Properties of a Service Wrapper

I always make a service wrapper, and I start it to suit whatever use-case is driving the integration. The service wrapper can be enhanced as the app needs it to, but it always represents exactly and only how the app uses the wrapped service.

These classes should have these properties to maximize their effectiveness:

- Methods should be named in the language of the service, not the language of the app.

- Arguments should use the domain of the service, not the domain of the app.

- Arguments should be whatever type is directly needed by the service, so passing in complex stuff like Active Record should be avoided.

- The return value should not be a complex object from the third party, but ideally only what data a caller will need (often nothing at all). If it must be a complex object, its name or properties should be in the domain of the service.

A class with the properties above can be more easily mocked in a test of a class that uses it. For example:

customer = create(:customer)

payment_method = create(:payment_method,

customer: customer,

stripe_id: "9876")

product = create(:product,

name: "Stembolt",

price_cents: 45_98)

shipping_method = create(:shipping_method,

price_cents: 4_32)

order = create(:order,

product: product,

customer: customer,

shipping_method: shipping_method)

stripe_charge_id = "12345"

allow(stripe_service_wrapper).to receive(

:create_and_confirm_payment_intent

).and_return(OpenStruct.new(id: stripe_charge_id))

subject.on_order_shipped(order)

expect(order.charge).not_to eq(nil)

expect(order.charge.stripe_id).to eq("12345")

expect(stripe_service_wrapper).to have_recieved(

:create_and_confirm_payment_intent

).with(

payment_method_id: "9876",

receipt_email: "pat@example.com",

description: "Purcahase of Stembolt",

amount_cents: 50_30,

example_co_id: order.charge_id,

)

This mock expectation is much clearer than if we’d mocked Stripe’s API client, since it only contains information relevant to our domain and this specific use-case.

This leaves the question of how to ensure the service wrapper itself is working.

Apply Multiple Techniques to Ensure the Service Wrapper Works

Regardless of how we model our integration, third party services always present a testing problem, since you can’t always call into the service directly, setting up HTTP-mocking systems is brittle and flaky, and mock-only unit tests don’t give much confidence.

Remember, tests are only one strategy available to ensure the proper functioning of our system. There are other techniques we can use. I find success combining these four techniques:

- The service wrapper pattern itself yields a class that has little or no branching or data transformation logic. The methods often look like example integration code and so tend to be pretty simple.

- A basic unit test of the wrapper that mocks the client or the HTTP library (but not HTTP itself) can make sure there’s no typos or syntax errors, as well as handle coverage of any branching that might be needed.

- At least one integration test of an end-to-end feature is set up to call into the actual service or it’s dedicated testing environment (assuming that’s possible). This might be flaky, but it’s only one test and allows you to call the service before shipping to production.

- Use background jobs for any codepath that will call the service wrapper. The jobs must be idempotent and you must have adequate monitoring of your background job system. If anything goes wrong, you’ll be notified, can fix it, and retry the jobs.

These techniques aren’t enough on their own. You have to bring them all together. The primary app I work on at the time of this writing has many third party integrations, and while I’ve certainly experienced a wide variety of failure modes, there has never been user impact and rarely business impact.

Next time you do an API integration, no matter how simple the API might seem, try creating a service wrapper.