Event Sourcing in the Small

August 14, 2019 📬 Get My Weekly Newsletter ☞

I’ve been fascinated by event-sourced architectures and wanted to get some real experience with it, but I also didn’t want to set up massive infrastructure inside AWS, find 100 developers to test it out on, and potentially ruin a business by doing so.

So I created an application that I believe mimics the developer workflows and architectural decisions you have to make in order to add features to an event-sourced architecture and want to share what I found. Anyone who has done this in the large, would love to hear if this tracks with your experience.

My takeaways are that it encourages some good practices, creates handy de-coupling between components, but introduces some friction, as well as complication for building a UI.

Let’s see how.

What is “Event-Sourcing”?

Martin Fowler has a good overview of the concept, but for me, I created an application where:

- All actions a user (or system process) takes generate events, and that’s it.

- Any feature that must query data (e.g. a UI) does so against a projection of the event stream (the event stream is never directly queried).

It’s, of course, possible to build an application based on these principles without having Apache Kafka and AWS Lambda set up, so that’s what I did. In the next section I’ll describe the application I built and how it works, mostly to give you a sense of the different parts when I talk about the experience developing for it (if you want to skip straight to my learnings by all means, go ahead :).

Each part of the application is inside a single app, but I think they behave like they would if they were “real” pieces of infrastructure.

The App

The app is a simple contact management app. You can:

- Add a new contact (name, description, contact method)

- Edit or delete a contact

- Record an interaction with a contact (e.g. record that you had coffee with Bob on the 13th)

- Write notes about your next meeting with a contact (e.g. to remind you to ask Sally about Postgres)

- View and sort contacts as well as past interactions

- Email you a copy of your notes that morning of a meeting

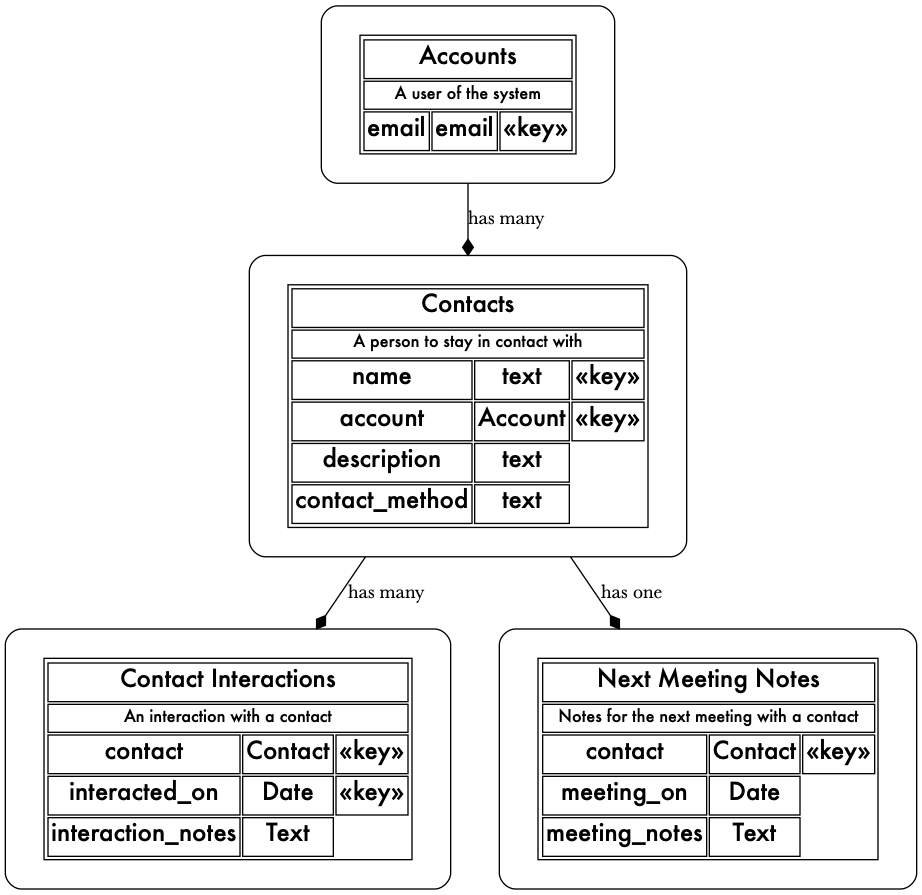

Here is the data model of the app:

To make such an app using a classic Rails approach would be pretty simple, and I don’t think anyone would suggest using event sourcing for such a simple app, but at this level of complexity, I still think I can get a good signal on what it would be like to work in a true event-sourced architecture.

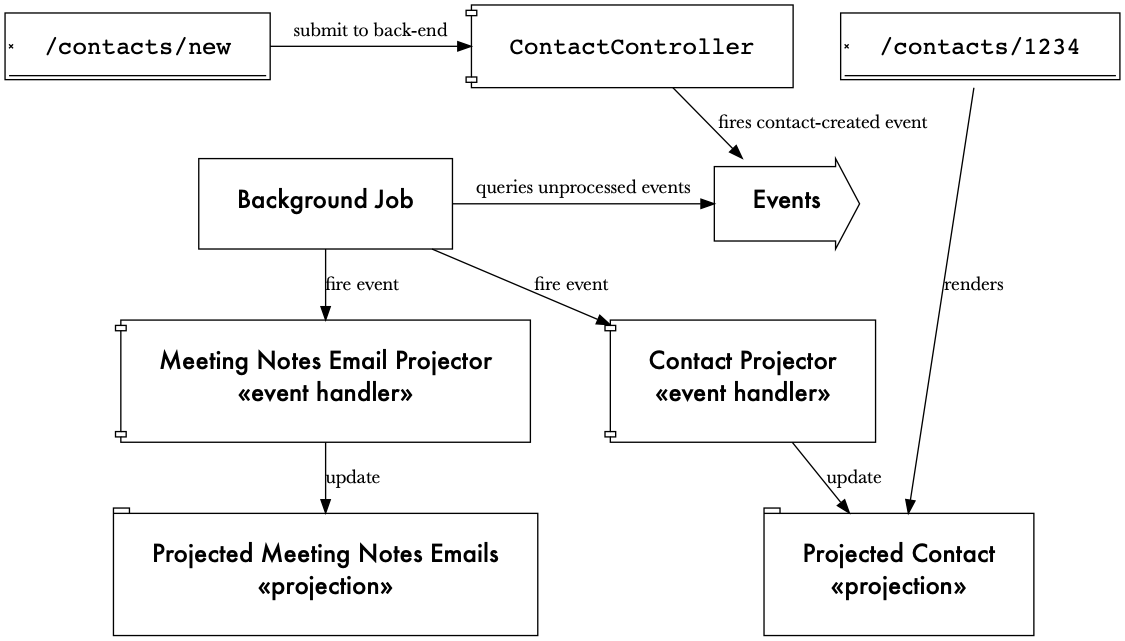

The URLs for the application all follow the Rails conventions around routes. So, adding a new contact does a POST to the /contacts endpoint. This convention is a reasonable way to organize routes. Where things differ is in

what goes into the controllers.

Each controller that represents a user action simply writes an event to an internal table called Events. The events table (below) stores a payload in JSON, a reference to an event type (e.g. “contact created”), a reference to

who triggered the event, which I called an entity, because I wanted it to be either a user of the system (account) or a system process. There’s also a creation timestamp (I’ll explain processed_at later).

CREATE TABLE events (

id bigint NOT NULL,

payload jsonb NOT NULL,

event_type_id bigint NOT NULL,

entity_id bigint NOT NULL,

created_at timestamp with time zone DEFAULT now() NOT NULL,

processed_at timestamp with time zone

);

Event types are associated with a JSON schema. They are also versioned so we can tell that a payload is version 1 of “contact edited” or version 2 (e.g.).

Below is the schema for the contact-created event type. If you haven’t seen JSON Schemas before, the schema below says that there must be keys for name, description, and contact_method, and that all three are required and that there may not be any other fields in the payload.

{

"$schema": "http://json-schema.org/draft-04/schema#",

"$id": "http://naildrivin5.com/crm/contact-created.json",

"title": "Contact Created",

"description": "Used when a contact has been created by an account",

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"name": {

"type": "string",

"description": "Name of the contact, however the account wishes to keep track of it"

},

"description": {

"type": "string",

"description": "A description of the contact, e.g. how they are known or who they are"

},

"contact_method": {

"type": "string",

"description": "However the contact should be contacted. Could be an email, url, or twitter handler or whatever."

}

},

"required": [ "name", "description", "contact_method" ],

"additionalProperties": false

}

When an event is fired, the application makes sure the payload conforms to the schema before storing it. The idea is that our events table should only have valid payloads.

In a real event-sourced system, the event infrastructure would handle notifying any listeners about the new event.

For my case, I did this with a background job. It polls for all events where processed_at is null. Any that

are, it fires a background job for each configured listener for each new event. Once it has queued those

background jobs, it sets processed_at on the event. This is an oversimplification of how it would work for

real, but also let me avoid a lot of complexity.

So this handles user and system actions that would change the data. What about querying the data?

For that, I stuck to Rails’ conventions on routing (e.g. a GET to /contacts shows all contacts), but this was

implemented by creating projections for each need. A projection is a view of the event stream that is

constantly updated based on the events coming in.

ON the screen that lists contacts, we need to know the name, description, contact method, last interaction date,

next meeting date, and next meeting notes. So, I created a table called projected_contacts that stores all

of that. When an event is fired that creates or updates a contact’s info, a listener will modify the

projected_contacts table to match.

CREATE TABLE public.projected_contacts (

id bigint NOT NULL,

name text,

description text,

contact_method text,

account_id bigint NOT NULL,

last_interacted_on date,

next_meeting_notes text,

next_meeting_at timestamp with time zone

last_updated_at timestamp with time zone NOT NULL,

);

-- name and account_id form the 'natural key'

-- of this table, thus we need a unique index

CREATE UNIQUE INDEX ON

public.projected_contacts

USING btree

(name, account_id);

If we create a contact named “Steve Jobs” with a description of “CEO of NEXT”, we’d write those values into the

projected_contacts fields name and description, respectively. Since the key is name and account, we first

check if there is a “Steve Jobs” in our account. If so, we update the row, if not we create it.

Later, if we change the description to “CEO of Apple”, that would result in a “contact edited” event being fired.

Our listener intercepts that event, locates the row in projected_contacts for Steve Jobs in our account, and

updates description to be “CEO of Apple”.

So, the projection stores a snapshot of the current state of the events.

This means that our controller simply queries this table and sends it to the view. No need for presenters or decorators or anything.

To see how we use the same events to accomplish a different task, you’ll remember I wanted the system to send an email with notes for the contact on the morning of a meeting.

While this could be accomplished by querying projected_contacts, I decided to make a second projection to

represent the emails that need to be sent. It’s called projected_meeting_notes_emails and contains only what’s

needed to fulfill that task: the contact name, the account, the meeting notes, and the date:

CREATE TABLE public.projected_meeting_notes_emails (

id bigint NOT NULL,

contact_name text,

account_id bigint NOT NULL,

meeting_notes text,

meeting_on date,

last_updated_at timestamp with time zone NOT NULL

);

A background job then queries this table and if the current date is the same as meeting_on, it sends an email to

the account holder with the notes. That sends an event called “meeting notes email sent” and a second

listener hears that and deletes the row so we don’t send the email again.

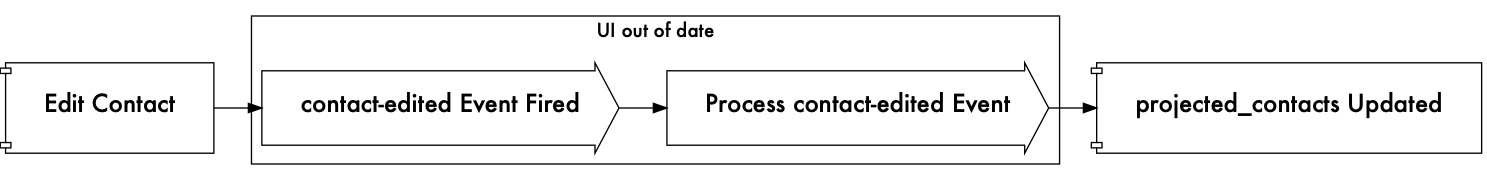

One last thing to mention. It’s natural to expect that if I edit a contact, when the page refreshes, I would see that contact’s updated data. In a classic CRUD application, this is trivial. In my event-sourced application because the editing action triggers an event, and the view is rendering a projection in the background, the view is out of date until the projection has been updated.

I initially tried to have the front-end poll for the change, but ultimately decided to do something simpler. After an event is fired, the controller redirects the user’s browser to a page that will show a “Processing…” message and refresh itself every so often to see if the projection has been updated. When it has, it redirects the user to the right page. It’s ugly. I’ll talk about it below.

So, this is generally how the application works. Below is an overview of the entire architecture.

So what did I learn from all this?

Learnings

My key takeaways were:

- More up-front data modeling is required, both for message schemas and the overall system domain model.

- There is less up-front design when adding a feature, because the projection concept separates concerns.

- There are a lot of moving parts.

- Keeping UIs up-to-date is a pain.

More Up-Front Data Modeling

There are two bits of up-front design that I felt were critical to working effectively in this system. The first and most obvious was the schema for the message payloads. I’ve worked in a distributed system that heavily used messaging and the lack of definition around payload contents (as well as the lack of development hygiene in sending those messages) was very difficult to deal with. Everyone ended up not changing their message payloads out of fear, and discovering payload contents by inspection. When an invalid message gets sent, it created problems that were hard to diagnose and fix.

The way to deal with this is to do a bit more up-front thinking about the schema for the messages and be relatively confident when you go to production that the schema is correct. You also have to have a good understanding of how you would change that schema in the future, along with a way to test everything.

The second bit about this is much more subtle and has to do with the domain model for the system being built.

Above, I showed a diagram of the logical domain model of my CRM app. But there are no tables in any database that look like that. In a classic CRUD-style app, your physical database schema is often a direct copy of your logical domain model. It’s just simpler this way, and you often want your underlying database to be properly normalized and thus free of duplication and confusion.

There’s no rule that says you ever have to manifest your domain model in a physical database, but if you don’t, you still need to maintain and understand that model.

This has two implications. First, you need to have it documented somewhere, and kept up to date. Second, you have to have a good understanding of logical domain modeling, specifically identifying what the natural (or business) keys are. For example, in my CRM app, a contact is uniquely identified by a name and an account.

The reason for this is that your projections aren’t going to be a normalized relational model. The way you locate data isn’t by a series of surrogate/synthetic keys, but by the natural keys. The events aren’t going to have database keys in them because they would not know them, so you have to look up data by the data itself.

There’s nothing wrong with this, but modern ORMs don’t encourage this sort of behavior, so it did feel a bit

strange. The upshot is you have to create indexes in your physical schema based on these keys so you can do the

lookups you are actually going to do (this is why I created an additional index in projected_contacts above).

It also means you have to be very careful with what you do with all those synthetic id fields. Ideally, you can

blow away all your projections and rebuild them from the event stream and the entire system still works. So for

example, if you email someone a link to your app, and that link has a synthetic id in it, that link will break

if you have to rebuild your projections.

Up-front thinking always feels painful and unproductive, but I do think a bit more rigor around data modeling is a good thing. My takeaway would be if I was confident in what I was building, this up-front design isn’t a big deal and probably is a good thing. If, on the other hand, I’m unsure what I’m building and need to experiment, pivot and make tons of changes, it feels like more of a hassle than a benefit.

That said, I think this does reduce the burden around adding new features.

Adding Features Requires a Bit Less Data Modeling

If you have a solid data model, and clear schemas for your events, adding a new feature is a bit simpler, because you create a new projection (or edit an existing one) for whatever data you need and expose that data to the view. Then you replay the events to populate your projection.

For example, I decided I wanted meeting notes to support Markdown. So I added a new field to the

projected_contacts projection to hold an HTML-rendering of the meeting notes. I modified the event handler to

render markdown into HTML and store it into that field. When I replayed all the events through that handler, I

had HTML-rendered meeting notes.

In a CRUD-style application, you might pick and choose the data from your normalized model to use, and create abstractions like presenters or decorators to make that code simpler. By using projections of events, you don’t need that abstraction, because the projection itself is the presenter. The controller is just sending data to a view.

This means that projection could be easily replaced with a cache or other data store without affecting the controller or view logic. Although my application is small, I can definitely see the advantages to this sort of separation on a larger app or larger team.

You could imagine a designer and front-end developer could entirely build their UI first. From that UI, you can identify what data you need in a projection. You then create that projection and implement a handler to populate it. In building that handler, you can determine if the event stream has the data you need.

The projection forms a contract between front-end and back-end, and while this is unnecessary at small scale, and medium or larger scale, it seems critical.

Of course, this comes at a cost as you can tell, which is a lot more moving parts.

Lots of Moving Parts

In a classic CRUD-style application, you have your normalized data model, which you hydrate into model objects, and controllers send those to a view which renders them. Perhaps your model objects get transformed through presenter objects. This is pretty easy to understand. Making a new view of an existing model is a matter of writing some presenter code, and that’s it.

Here, to make a new feature, you have to:

- Create the view

- Create and model any new events you might need

- Update all your event handlers to see if they need to handle this new event

- Create or modify a projection

- Create or modify a handler to deal with the projection

- Ensure that the event stream is played into the handler to update/populate the projection

- Create a controller to query that projection

That’s a lot more work! Granted, some of this can be scaffolded with code generation (I created a few Rails generators to do this), but it’s still a lot more moving parts, each of which must be tested and developed.

At a small scale, this feels painful. At a larger scale, though, I can see the advantages to this level of separation.

But none of this was as painful as keeping the UI updated.

Updating the UI is Painful

This is a classic case of “stupid computer”. Of course when I edit a contact, my edits should show up when I view that contact. And in a CRUD-style application, that’s what happens, because the code that handles the edit writes to the data store that the code showing the data reads from.

Here, the data has to go through an event, then through a series of background jobs and handlers before a projection gets updated and then our UI is correct again. UGH.

The core problem is that a UI can’t always know what events might cause it to become out of date, and it’s often unacceptable to the user experience to show out-of-date data.

The way I approached this was as follows:

- There is a table called

projectionsthat stores all known projections and when they were last updated. - Every handler that updates a projection bumps this date, even if it’s ignoring an event.

- All UI is based on a single projection, and so it can know when the data it is showing was last updated.

With this in place, if the user took an action that fired an event, I would redirect the user to the view they should see after the update, but include the event’s creation date in that redirect. The view would see this, compare it to the last update date of its projection, and only send the user through to the view when the projection had been updated.

There are all sorts of problems with this that, at scale, would be hard to manage. If my background jobs all died, the user would be perpetually stuck on this screen. An entire user experience has to be designed around this reality. It complicates the front-end greatly.

Now, to be fair, even in a more classic synchronous CRUD-style application, you eventually have this problem. Many UIs at Stitch Fix have this issue and are dealt with in a variety of ways (some good, some not so good).

But the point here is that on day zero you have to solve this UI problem. And it’s painful.

This is a good example of an iceberg of complexity at a larger scale.

Where More Complexity Lies

A “real” event-sourced system would have a shared messaging infrastructure and several consumers. It would be more distributed and I can only imagine the complexity in having to keep track of how far into the event stream they had processed.

Further, as time goes on, it’s harder and harder to replay they entire event stream in a reasonable amount of time. And then there’s dealing with versioning issues. What happens when today’s event handler is given yesterday’s schema for an event? For that matter, how do I know if I introduce a change to an event, it doesn’t take down an entire subsystem. How do we really test all this?

Despite this, there is something appealing about the separation this gives you as well as the ability to go back and play history through a new lens. For financial reporting it seems like a boon (though for data privacy stuff like GDPR, I don’t know how you deal with it).

The hardest part for me is knowing when to use this. It creates a lot of friction for a small application, but all applications start small. Moving to an event-sourced architecture when your application (and team) is no longer small feels like a big undertaking that could be hard to justify.

Anyone have experiences to share?