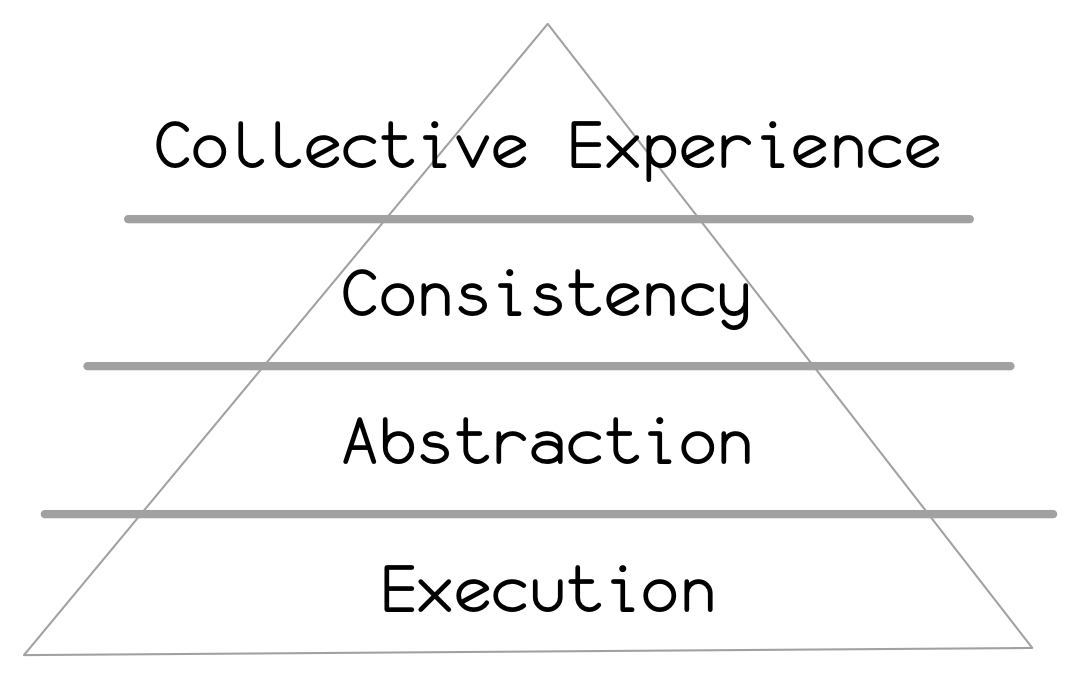

Hierarchy of Software Needs

January 13, 2016 📬 Get My Weekly Newsletter ☞

If you regularly work with web technologies, you’ve no-doubt pulled your hair out dealing with the technologies used for front-end development (and, let’s be honest, back-end development, too :). Almost everything about front-end work feels terrible, from the weakness of JavaScript as a language, to the myriad half-documented tools that all somehow manage to do less than make, to the absolute bizarre notion that we are building user interfaces with technologies designed to write term papers.

But why are these experiences unpleasant? I would argue simply that they don’t fully meet our needs as programmers. And we can think about those needs as a hierarchy, each need building on the need below it.

Hierarchy of Needs?

If you aren’t familiar with Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, it describes a psychological hierarchy of increasingly powerful needs that, when met, contribute to healthy mental well-being.

At the bottom are basic needs like air, food, and water—called physiological needs—that we all need to merely be alive. The next step are safety needs, which we fulfill after our physiologic ones. These are needs like physical or financial safety, the absence of which can cause stress and anxiety.

Next is our need for love and belonging which contribute to our abililty to form relationships with others. After this comes self-esteem or self-respect, which allow us to feel a sense of contribution and value.

The top of the hierarchy is self-actualization, which represents our desire and ability to achieve all that we can.

What I’ve laid out is an extremely simplified summary and it’s for context only. It’s a framing concept for talking about the Hierarchy of Programming Needs.

Our Needs as Programmers

Here are our needs as programmers. The bottom are our most basic needs, which must be met before needs higher up the pyramid can be met.

The most basic thing we need as programmers is the ability run, or execute, our code.

Need to Execute Code

Code that can’t be executed might as well not exist. It can never serve much purpose if we can’t run it. Running code is like breathing—there’s no job called “Programmer” if code can’t be executed.

Just as with our physiological needs, our executable needs as programmers can be met with varying degrees of utility. Technically, loading a BASIC program

from a floppy disk and typing RUN meets our need. But not in the same way as a REPL that has a command-line history and code completion.

Either way, if all we can do is run code, we won’t get far. Anything remotely complex will be a disaster of confusion, un-maintainability, and errors. We need to manage that complexity, and the most basic way to do that is by creating abstractions.

Need to Create Abstractions

It’s difficult to understand and modify a large codebase. By creating abstractions we have a hope of doing so. An abstraction is any way to create a higher-level construct. It could be as simple as functional decomposition or creating data types. It could be as complex is an advanced type system, pattern matching, or inheritance.

Regardless, we have no hope of successfully writing and managing computer software without some way to create and use abstractions. As with our need to execute code, our need to create abstractions can be met in a variety of ways. Technically, jumping to a pre-defined memory location that contains a subroutine is a form of abstraction. This is far less convenient than calling a named function.

When our need for abstracting code is met, we can accomplish a great deal. But the moment we must collaborate with another person (including ourselves in the future!), we’ll run into problems. With two distinct minds working on a piece of software, there will be different ways to accomplish things, different possible abstractions. This leads to inconsistency, which makes a codebase hard to deal with, as you must understand more than you need to.

Need for Consistency

Sometimes, the lack of consistency is merely annoying. Sometimes, however, it can be disastrous. We’ve all heard about the Mars probe that crashed because half the team was using Metric and the other half Imperial. Their need for consistency wasn’t being met, and all the great abstractions in the world couldn’t help.

The way to manage consistency is to establish conventions, but they need to be put into code. The need for consistency is only met when it’s difficult (or ideally impossible) to circumvent conventions and be inconsistent.

For example, here are two ways to define a function in JavaScript:

foo = function() { }

function bar() { }

If we wish to use the latter form as our convention, we have no way to enforce or even encourage it in JavaScript. In this regard, JavaScript is not meeting our need for consistency.

Think about the Mars probe. Ideally, it would not have been possible to use two measurement systems. Their programming environment had no way to meet that need and a timely, expensive scientific research mission utterly failed.

Take a moment here to reflect. It was pretty hard to imagine any programming environment, tool, or language that didn’t meet our first two basic needs of executing code and creating abstractions. But now, we’re starting to see that our deeper needs (like consistency) aren’t that easy to meet.

But, supposing we could meet our need for consistency. This would lead to many teams and many codebases, all self-consistent and easy to work in, but all different. Working on a new system requires starting over and learning many new things in order to be productive.

While some of this is natural—the domain of a new system might be unfamiliar—some of it is not (e.g. most systems need logging).

The reality is that teams and software systems face many of the same problems, and those problems often have few, or even one, reasonable solution. We spend time going to conferences and reading books & blogs in order to learn about these solutions, to share them with others, and try to pass them on to the next generation. We have a need for collective experience.

Need for Collective Experience

How many teams are suffering through the exact same problem right now? How many are re-discovering the same solution to the same problems that have been solved years earlier?

If you’ve payed close attention during the birth of new and popular software tools, you’ve seen this. Ruby on Rails’ journey from upstart framework to accepted enterprise software platform has included (but, to be fair, not been dominated by) a pointless journey in re-learning many lessons of the previous decade’s Java and J2EE developers (who themselves no-doubt re-learned lessons from the previous generation of C++ developers). NodeJS and the ecosystem of front-end tooling is repeating this.

This isn’t a knock on these communities: this is a hard need to meet. The current state of the art—reading books, using tried-and-true-but-boring programming languages, and going to conferences—isn’t cutting it. Have you ever created a log format for your application log?

When our need for collective experience isn’t met, it can be worse than merely re-implementing solutions and re-learning lessons. We often regress.

By any objective measure, XML and a Schema is more powerful than JSON. Yet, XML is the butt of many jokes and is generally avoided by many developers. Those

same developers are writing documentation to explain that an address key in a JSON payload should map to an object containing street, city, state, and zip keys (all Strings) so everyone knows what to expect when making an API call.

This was 100% solved in software in the late 90’s. We’re now seeing stuff like JSON Schema crop up as everyone realizes that many of XML’s features are actually really useful.

But the failure here isn’t those developers using JSON. We all embraced JSON because while XML as a specification and a format is great, the ways in which we interacted with it were (and are) terrible. The community around XML was unable to meet our need for collective experience.

Like I said, this is a hard need to meet. It feels almost impossible.

But, thinking about this need can be instructive. It can drive us to make better decisions about software design, about tool design, about language design! Why does the Go language have first-class support for goroutines and channels? Because the language designers are trying to pass on their collective experience about how to deal with concurrency.

And now, back to reality

Think about the tools you use each day when programming. How well do they meet your needs as a programmer? JavaScript barely meets our need for abstractions. CSS doesn’t even meet that!

Think about Ruby on Rails: it bakes in many conventions. Have you ever been on a Rails project and discussed how to name database keys? Or how to name controllers? It is meeting our need for consistency (in those areas :).

And UNIX: The convention around “everything is a stream of bytes” is not only baked into the shell and the included tools, but it’s the foundation of I/O in almost every language in use. Talk about collective experience!

But, what does this all mean?

On the one hand, we are far too accepting of tools that barely meet our needs. But, I also think that if we start to think about what our needs are, it can drive us to make better decisions about the software we use and the code we write.